To determine the perception and management of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) by clinical cardiologists and to establish a consensus with recommendations.

MethodsWe employed the modified Delphi method among a panel of 150 experts who answered a questionnaire that included 3 blocks: definition and perception of patients with “stable” HFrEF (15 statements), management of patients with “stable” HFrEF (51 statements) and recommendations for optimising the management and follow-up (9 statements). The level of agreement was assessed with a Likert 9-point scale.

ResultsA consensus of agreement was reached on 49 statements, a consensus of disagreement was reached on 16, and 10 statements remained undetermined. There was consensus regarding the definition of “stable” HF (82%), that HFrEF had a silent nature that could increase the mortality risk for mildly symptomatic patients (96%) and that the drug treatment should be optimised, regardless of whether a patient with HFrEF remains stable in the same functional class (98.7%). In contrast, there was a consensus of disagreement regarding the notion that treatment with an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor is justified only when the functional class worsens (90.7%).

ConclusionsOur current understanding of “stable” HF is insufficient, and the treatment needs to be optimised, even for apparently stable patients, to decrease the risk of disease progression.

Conocer la percepción y el manejo del cardiólogo clínico de la insuficiencia cardiaca con fracción de eyección reducida (IC-FER) y establecer un consenso con recomendaciones.

MétodosSe empleó el método Delphi modificado entre un panel de 150 expertos, que respondieron un cuestionario que incluyó tres bloques: definición y percepción del paciente con IC-FER «estable» (15 afirmaciones), manejo del paciente con IC-FER «estable» (51 afirmaciones) y recomendaciones para optimizar el manejo y seguimiento (9 afirmaciones). El nivel de acuerdo se evaluó utilizando una escala tipo Likert de 9 puntos.

ResultadosSe llegó a un consenso de acuerdo en 49 afirmaciones, a un consenso en el desacuerdo en 16 y quedaron indeterminadas 10 afirmaciones. Hubo consenso en cuanto a la definición de IC “estable” (82%), en que la IC-FER tiene una naturaleza silenciosa que puede contribuir a aumentar el riesgo de muerte en pacientes poco sintomáticos (96%), y que independientemente de que el paciente con IC-FER se mantenga estable en la misma clase funcional el tratamiento farmacológico debe optimizarse (98,7%). En cambio, hubo consenso en el desacuerdo con respecto a que el tratamiento con un inhibidor de neprilisina y receptor de angiotensina solo está justificado cuando hay un empeoramiento de la clase funcional (90,7%).

ConclusionesEl conocimiento actual sobre la IC “estable” es insuficiente, siendo necesaria la optimización del tratamiento, incluso en pacientes aparentemente estables para disminuir el riesgo de progresión de la enfermedad.

Heart failure (HF) is a severe clinical syndrome caused by a structural or functional cardiac anomaly that can be present before the onset of symptoms.1–4 “Stable” HF has classically been defined as the absence of clinical deterioration or changes in medication and an absence of hospitalizations.5 However, it is well known that HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is a progressive disorder that is not always detected clinically.6,7 In fact, patients with “stable” HF have a 1-year all-cause mortality rate of 7.2% and a 1-year hospitalization rate of 31.9%.8,9

Managing HF is complex due in part to the presence of comorbidities.10 The treatment algorithm for patients with HFrEF includes angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin II-receptor blockers (ARBs), beta blockers and aldosterone antagonists. In recent years, 2 new drug treatments have emerged for HFrEF: ivabradine and angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI).1,2 Although the survival of patients with HFrEF has improved in recent years, the results are still insufficient.2,11 Given the need to raise awareness about the risk these patients present and to better understand the diagnostic and therapeutic management of this disease by clinical cardiologists, we conducted this study to establish recommendations on improving the management of outpatients with HF.

MethodsStudy designThe Outpatient Heart Failure in Apparently Stable Patients: Challenges and Management Guidelines (Insuficiencia Cardiaca en consulta amBulatoria en paciente aparentemente Estable: Retos y Guía de manejo, IC-BERG) study, sponsored by the Research Agency of the Spanish Society of Cardiology, was conducted following the modified Delphi method12 to reach a consensus on the management of patients with HFrEF treated in cardiology consultations. The modified Delphi method is a structured technique for remote professional consensus, a variant of the original procedure that keeps the main advantages (controlled interaction between panel members, opportunity to reflect on and reconsider the opinion itself without losing the anonymity and statistical validation of the achieved consensus) over other techniques and resolves a number of its main disadvantages (opinion biases).

The study was conducted in 5 phases: 1) composition of the scientific committee, 2) preparation of the questionnaire, 3) selection of the expert panel, 4) administration of the questionnaire and 5) data collection, analysis and interpretation of results.

Composition of the scientific committeeThe scientific committee, formed by 6 members with extensive professional experience in clinical cardiology, created the questionnaire, selected the expert panel and analyzed the results.

Preparation of the questionnaireTo this end, we conducted a relevant literature search in the MEDLINE, EMBASE and Spanish Medical Index (Índice Médico Español) databases13 to identify the aspects of HF that could be of interest to the study. From this information, the committee created the final questionnaire, which consisted of 75 statements (Supplementary Table 1). Each statement had a Likert 9-point scale assessment grouped into 3 levels: completely disagree or not at all appropriate (1–3), neutral (4–6) and completely agree or completely appropriate (7–9).

The statements were organized into 3 sections: A. Definition and perception of patients with “stable” HFrEF (15 statements). B. Management of patients with “stable” HFrEF (51 statements). C. Recommendations for optimizing the management and follow-up of patients with “stable” HFrEF (9 statements).

Selection of the expert panelThe scientific committee of the IC-BERG study selected the participating panelists from a database. This selection was performed strictly based on the participants’ experience in the area of clinical cardiology. A total of 150 cardiologists throughout Spain participated in the project (Supplementary Table 2). The selection criteria were as follows: clinical cardiologists not assigned to a specialized HF consultation unit in their standard practice, more than 2 years of experience after completing the training period, working at least 2 days a week in the outpatient office and having treated more than 20 patients with HF in the past 3 months (more than 7 a month) (Supplementary Table 2).

Administration of the questionnaireThe questionnaire was submitted to the expert panel through an online platform that ensured data confidentiality. The data were collected between January and March 2019. The 150 panelists freely answered all questions in both rounds, with no external influence on the answers of the questionnaire.

Analysis and interpretation of resultsWe performed a descriptive analysis of the results for each statement in the questionnaire and grouped the responses for each statement into 3 levels: 1–3, 4–6 and 7–9. We defined “consensus in agreement” when at least 70% of the experts assessed the statement with scores of 7–9 and “consensus in disagreement” when at least a 70% of the experts assessed the statement with scores of 1–3.14 The other options were defined as “consensus not reached”. To perform the comparative analysis between the 2 rounds, we employed the Bowker test15 and established the bilateral level of statistical significance at 0.05. The data were analyzed with the SPSS statistical package v.22.

ResultsSupplementary Table 2 shows the panelists’ characteristics. Twenty-four percent of the participants had more than 20 years of professional exercise caring for patients with HF, with a mean of 3.41 days of consultations per week. Fifty-eight percent cared for 16–50 patients with HF per month. The panelists indicated that 55.7% of the patients they treated had “stable” HFrEF.

Supplementary Tables 3–5 show the complete results of the Delphi questionnaire, while Tables 1 and 2 show the statements for which consensus in agreement or disagreement was achieved after the 2 rounds, divided according to the various analyzed blocks. In the first round, the panelists achieved consensus on 59 statements (46 in agreement and 13 in disagreement). The 16 remaining statements were subjected to a second round of votes. In the second round, consensus was reached on 6 of the 16 reconsulted statements (3 in agreement and 3 in disagreement). Therefore, by the end of the Delphi process, consensus was reached on 65 statements (49 in agreement and 16 in disagreement), with 10 statements undetermined. The tables indicate the significance of the Bowker test for comparing the results of the 2 rounds (a p-value <.05 indicated that the responses of the 2 rounds were significantly different).

Definition and perception of patients with “stable” HFrEF: items that achieved consensus in the first or second round of Delphi.

| % consensus in agreement | p (Bowker Test) | |

|---|---|---|

| [0,1–3]Definition of HFrEF | ||

| HFrEF: Clinical diagnosis of HF and LVEF ≤ 40%. HF is a complex clinical syndrome that results from any structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or of blood ejection. The cardinal manifestations of HF are dyspnea and fatigue, which can limit exercise tolerance, and fluid retention, which can lead to pulmonary congestion and splanchnic or peripheral edema. (ACC/AHA/HFSA guidelines). | 92.7% | N/A |

| HFrEF: Clinical diagnosis of HF and LVEF ≤ 40%. HF is a clinical syndrome characterized by typical symptoms (such as dyspnea, fatigue and inflammation of the ankles), which can be accompanied by signs (such as high jugular venous pressure, crackles and peripheral edema) caused by a structural or functional cardiac anomaly that result in reduced cardiac output and increased intracardiac pressures at rest or under stress. (2016 ESC Guidelines) | 92% | 0.783 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Definition of “stable” patient with HFrEF | ||

| In a patient with chronic HF, the term “stability” usually refers to the fact that signs and symptoms are nonexistent or mild and have not changed recently or at least in the past month or since the last medical visit according to clinical practice. | 82% | 0.001* |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]“Stable” HFrEF and current standard clinical practice | ||

| The silent but progressive nature of HFrEF can contribute to an increased mortality risk for patients who are asymptomatic or only slightly symptomatic. | 96% | N/A |

| The recently developed risk calculators take into account the next-generation treatments and biomarker levels and reveal that there is no true stable HF. | 71.3% | 0.909 |

| HFrEF is a progressive disorder in which the cardiac structure and function continue to deteriorate, often despite the absence of clinically apparent signs and symptoms of worsening of the disease. | 70.7% | N/A |

| “Stable” HFrEF and current standard clinical practice | % consensus in disagreement | |

| Patients with symptomatic HF at some point (stage C of the ACC/AHA classification) who show no signs and symptoms during the clinical visit do not have a considerable mortality risk. | 95.3% | N/A |

| The silent but progressive nature of HFrEF does not contribute to an increased mortality risk for patients who are “clinically stable”. | 94% | N/A |

| The number of hospitalizations does not decline if the patient with HFrEF has optimized treatment. | 92.7% | N/A |

| In the short/medium term, it is unusual for patients with “stable” HFrEF to be hospitalized. | 70.7% | 0.186 |

Abbreviations: ACC/AHA, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; N/A, not applicable; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

*p < .05.

Management of patients with “stable” HFrEF: items that achieved consensus in the first or second round of Delphi.

| p (Bowker Test) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Assessment and follow-up of patients with “stable” HFrEF in current standard clinical practice | % consensus in agreement | |

| The follow-up of patients with “stable” HFrEF requires full collaboration between cardiologists and primary care physicians. | 99.3% | N/A |

| Nursing plays a key role in promoting treatment compliance. | 96.7% | N/A |

| Having a reference HF unit can be useful for managing patients with HFrEF. | 94.7% | N/A |

| Patients with difficult-to-control HFrEF should be followed-up in an HF unit. | 94.0% | N/A |

| The functional class can be the same, but “stable” HFrEF can progress. | 94.0% | N/A |

| Having a palliative care unit can be useful for managing patients with HFrEF. | 92.7% | N/A |

| Primary care physicians are indispensable for the optimal management of patients with “stable” HFrEF. | 92.0% | N/A |

| Assessing the signs and clinical symptoms is not sufficient for assessing the progress of patients with “stable” HFrEF. | 91.3% | N/A |

| Nursing plays a key role in detecting whether the signs or symptoms of HFrEF interfere with the patient’s daily life. | 90.7% | N/A |

| In consultation, patients with “stable” HFrEF should be specifically asked about each sign and symptom and how they affect the patients’ quality of life. | 88.0% | N/A |

| Patients with “stable” HFrEF should be examined at least every 6 months to assess whether their disease has worsened, whether their medication should be changed and whether other types of procedures should be considered. | 84.7% | N/A |

| Nursing plays a key role in detecting whether the treatment needs to be changed. | 82.0% | N/A |

| The need for adding or increasing the dosage of a loop diuretic indicates that the patient has ceased to be stable. | 80.0% | N/A |

| Assessment and follow-up of patients with “stable” HFrEF in current standard clinical practice | % consensus in disagreement | |

| In the consultation, assessing whether patients with “stable” HFrEF adjust their life as their physical capacity decreases is not necessary. | 96.7% | N/A |

| Magnetic resonance imaging of the heart is an essential technique to assess whether there is progression of the “stable” HFrEF. | 85.3% | 0.007* |

| Primary care physicians cannot perform rigorous follow-ups nor can they detect the progression of “stable” HFrEF. | 84.7% | N/A |

| To assess the progression of patients with “stable” HFrEF, measuring biomarker levels (such as natriuretic peptides) is not necessary. | 76.7% | N/A |

| Any patient with heart failure should be followed-up in a heart failure unit. | 74.0% | N/A |

| The functional classification of the NYHA scale is an objective assessment. | 73.3% | N/A |

| Treatment of patients with “stable” HFrEF in current standard clinical practice | % consensus in agreement | |

| During each visit, it is essential to assess the treatment compliance of patients with “stable” HFrEF. | 98.7% | N/A |

| Regardless of whether the patient with HFrEF remains in the same functional class, their drug treatment should be optimized. | 98.7% | N/A |

| The medical therapy of patients with “stable” HFrEF can be optimized with the new scientific advances. | 95.3% | N/A |

| The incorporation of new drugs in less symptomatic patients can slow the subclinical progression of the disease. | 95.3% | N/A |

| If a patient with HFrEF presents mild but persistent signs or symptoms that affect their quality of life, a change in treatment needs to be assessed. | 95.3% | N/A |

| Regardless of whether the patient with HFrEF remains “stable”, their drug treatment should be titrated to the target dosage. | 94.7% | N/A |

| If the patient with HFrEF remains symptomatic despite maximum tolerated dosages, a change in treatment is required. | 84.0% | N/A |

| The need for adding or increasing a diuretic indicates that the patient has ceased to be stable. | 79.3% | N/A |

| The change from an ACEI or ARB to an ARNI should not be reserved until clinical decompensation occurs. | 71.3% | N/A |

| Treatment of patients with “stable” HFrEF in current standard clinical practice | % consensus in disagreement | |

| Treatment with ARNI for patients with “stable” HFrEF is justified only when the functional class worsens. | 90.7% | N/A |

| If a patient with HFrEF presents mild but persistent signs or symptoms, a change in treatment does not need to be assessed. | 88.0% | N/A |

| Optimizing the treatment consists exclusively of titrating to the maximum tolerated dosage. | 74.7% | N/A |

| If a patient with HFrEF presents no signs or symptoms, a change in treatment does not need to be assessed. | 74.7% | N/A |

| The various comorbidities that patients with “stable” HFrEF can experience do not limit the ideal treatment. | 72.7% | N/A |

| When treating patients with “stable” HFrEF, experience should prevail over the guideline recommendations. | 70.0% | 0.029* |

| Approach for patients with “stable” HFrEF in current standard clinical practice | % consensus in agreement | |

| Specifically ask whether the patient with “stable” HFrEF feels more or less fatigue than in the previous visit. | 96.7% | N/A |

| Specifically inquire as to whether the patient with “stable” HFrEF has reduced their activity or has ceased some activity. | 95.3% | N/A |

| Specifically ask whether the patient with “stable” HFrEF suffocates more or less at night than in the previous visit. | 95.3% | N/A |

| Specifically inquire as to whether the patient with “stable” HFrEF tires more or less than in the previous visit. | 94.0% | N/A |

| Specifically inquire as to whether the patient with “stable” HFrEF has retained fluids. | 92.7% | N/A |

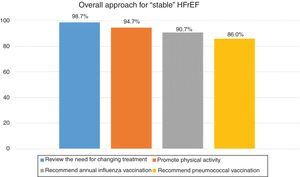

| Recommendations for the approach for patients with “stable” HFrEF in current standard clinical practice | % consensus in agreement | |

| Encourage and verify treatment compliance. | 100.0% | N/A |

| Review the need for changing the treatment. | 98.7% | N/A |

| Recommend weight control, if necessary. | 96.0% | N/A |

| Encourage healthy habits with self-care measures (blood pressure and heart rate). | 96.0% | N/A |

| Stimulate physical activity appropriate for the patient with HF. | 94.7% | N/A |

| Recommend an annual influenza vaccination. | 90.7% | N/A |

| Recommend a pneumococcal vaccination. | 86.0% | N/A |

| Recommendations based on clinical experience with patients with “stable” HFrEF | % consensus in agreement | |

| Awareness needs to be raised regarding the need for optimizing the treatment of patients with “stable” HFrEF. | 100% | N/A |

| Healthcare practitioners should be up-to-date on the latest therapeutic advances. | 100% | N/A |

| Awareness needs to be raised regarding the progression of “stable” HFrEF. | 99.3% | N/A |

| Continuity of care and coordination between cardiology and primary care need to be encouraged. | 99.3% | N/A |

| Healthcare practitioners should have useful tools for assessing the progression of HFrEF. | 99.3% | N/A |

| Healthcare practitioners should be trained to identify the progression of HFrEF. | 99.3% | N/A |

| Patients should be educated as to the importance of treatment compliance for HFrEF. | 99.3% | N/A |

| Healthcare practitioners need to be sensitized regarding compliance with the management guidelines for patients with “stable” HFrEF. | 98.0% | N/A |

| The clinical interview between the healthcare practitioner and patient with HFrEF should be protocolized. | 77.3% | N/A |

Abbreviations: ACC/AHA/HFSA, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Failure Society of America; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II-receptor blockers; ARNI, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; HF, heart failure; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; N/A, not applicable.

*p < .05.

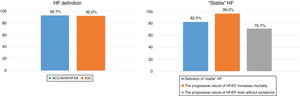

In terms of the definition and perception of patients with “stable” HFrEF (Table 1, Fig. 1), there was a high degree of consensus in terms of the definition of “stable” HF (82% of panelists) and that HFrEF has a silent nature that can increase the mortality risk for patients who are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic (96%). There was also a high degree of consensus in disagreement in that patients with symptomatic HF do not have a considerable mortality risk if they do not present marked signs and symptoms of HF (95.3%).

Percentage of consensus in agreement on the definition of heart failure and on the nature of “stable” heart failure.

Abbreviations: ACC/AHA/HFSA: American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Failure Society of America; ESC: European Society of Cardiology; HF: heart failure; HFrEF: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

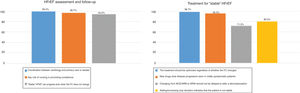

With regard to the management of patients with “stable” HFrEF (Table 2, Figs. 2 and 3), there was broad consensus in that cardiologists and primary care physicians should fully cooperate in the follow-up of these presumably “stable” patients (99.3%), that nursing plays a key role (96.7%) and that having a reference HF unit can be useful (94.7%). There was also a high degree of consensus in that the drug treatment should be optimized, even when the patients with HFrEF remain in the same functional class (98.7%), and that the need for adding or increasing a diuretic indicates that the patient has ceased being stable (79.3%). There was a high degree of consensus in disagreement regarding the notion that it is not necessary to assess in consultation whether the patient with “stable” HFrEF adjusts their life as their physical capacity reduces (96.7%) or that treatment with ARNI for patients with “stable” HFrEF is justified only when there is a worsening of the functional class (90.7%).

Percentage of consensus in agreement on the assessment, follow-up and treatment of “stable” HFrEF.

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; ARNI, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor; FC, functional class; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

Mortality for HFrEF remains high, and therefore improving its management is essential. This study shows the consensus that “stable” HFrEF is not a banal process but rather one that is associated with a high risk of disease progression. Raising the awareness of healthcare practitioners as to this fact is therefore necessary, as is the consequent need to optimize the treatment and follow-up of these patients.

One of the most relevant aspects revealed by this study’s results is the lack of agreement regarding the definition of “stable” HFrEF, given that consensus in agreement was reached in only 1 of the 3 definitions, which indicates that the current understanding of this entity is truly uncertain. This lack of consensus might be due, among other reasons, to the fact that “stable” HF as such does not exist, because in reality HF continues to progress.16–18 On this issue, the experts reached consensus in that disease progression can occur without changes in the functional class, given that progression is not directly related necessarily with functional class. The NYHA classification was also considered by the panelists as a subjective assessment of the patient’s symptoms and exercise capacity, given the lack of correlation between the NYHA functional class indicated by the physician and that considered by the patient.19 Therefore, assessing patients with HF through the simple functional class assessment could be insufficient. In short, these results lead to the notion that for experts the concept of stability in HF is incorrect. Rather, HF is a chronic disorder with periodic destabilizations that requires treatment optimization.

Another relevant aspect is that despite the fact that numerous studies have shown a high risk of sudden death in patients with HFrEF and a not very advanced functional class,17,18 the expert panel did not reach consensus on this issue, which could lead to a lack of treatment optimization.

A question that typically arises among physicians who treat patients with HF is whether patients who require diuretics to maintain the euvolemic state should really be considered “stable”. In fact, the expert panel did not reach consensus on this point, only that an increase in loop diuretic dosage indicated that the patient ceased to be “stable”. However, studies have indicated that patients with no signs of congestion who are treated with larger dosages of diuretics have higher mortality.20,21 Therefore, a patient who requires diuretics should not be considered a “stable” patient.

To optimize patient follow-up, a proper and timely patient assessment is required. The NICE guidelines recommend examining patients with “stable” HF at least every 6 months.5 In our study, the experts reached a high consensus in agreement with this recommendation. The panel also reached a consensus that performing a basic clinical assessment is insufficient and that patients should be asked during each visit whether they have had “new” symptoms and whether they have adjusted their life to these symptoms.

The current clinical practice guidelines recommend measuring natriuretic peptide levels to assess disease severity, establish the prognosis and prevent the progression of HF.1,2 The reduction in natriuretic peptide levels with treatment has been associated with lower HF mortality and lower hospitalization rates.22,23 In this respect, the experts achieved consensus on the need for measuring biomarker levels during follow-up, which could help optimize the treatment.

A low distance travelled in the 6-min walk test is an unfavorable prognostic marker of HF,2 and there is an inverse correlation between the functional class and distance travelled.24 However, the experts did not reach consensus on the need for the 6-min walk test for the patient’s clinical assessment in clinical cardiology consultations. The experts also considered that cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was not an essential technique for assessing stable HFrEF. Despite the fact that cardiac resonance imaging provides relevant information, it was not considered essential, especially for the follow-up.2,25 Although appropriate treatment of HF can improve the ejection fraction26 and lack of improvement is associated with a poorer prognosis,27 the experts did not reach consensus on the need for measuring the ejection fraction during the follow-up. Accordingly, the need for optimizing the treatment of HF will probably not depend on imaging tests as much as on clinical assessments.

The experts reached consensus in agreement with all statements related to the follow-up from the various healthcare departments, confirming that the follow-up of patients with HFrEF should be coordinated between the various healthcare levels, promoting continuous medical education necessary for improving the management of these patients.2,3 Appropriate coordination between the healthcare levels has been shown to improve the prognosis of patients with HF and reduce hospitalizations.28 Moreover, the clinical management depends on the healthcare resources and organization and should be adapted to each patient’s characteristics.29 The clinical cardiology section is developing the Management of Heart Failure in Cardiology and Primary Care (MICCAP) program, whose main objective is to improve the coordination between primary care and cardiology to improve the care of patients with HF.30

The objective of optimized treatment is to slow the disease progression and to improve the patients’ quality of life and prognosis.2,31 Thus, the experts reached consensus that a change in treatment needs to be assessed, regardless of the patient’s alleged clinical stability and maintenance of their functional class. For example, the expert panel reached consensus that the change from an ACEI or ARB to an ARNI should not be delayed until a clinical decompensation or worsening of the functional class, given that this is associated with a poorer prognosis and loss of opportunity for optimizing the treatment in the consultation. In fact, ARNIs have been shown to be superior to ACEIs (enalapril) in reducing the risk of mortality and hospitalization for patients with HFrEF who were mostly in NYHA functional class II/IV32,33 and is one of the recommendations in the clinical practice guidelines.2,31

As with other studies with a similar design, this study had a number of potential limitations worth mentioning. The experts were selected only from Spain, and all panelists were within the specialty of clinical cardiology. Although this could entail a certain territorial or specialty bias, the panelists were chosen for being experts on the subject. This consensus therefore did not consider the opinion of other practitioners who might also have contact with this disease. Lastly, the study’s strengths include the large number of participants (150 experts) and the recognized usefulness of the Delphi method for reaching conclusions, given that it ensures anonymity and that participants have sufficient time for individual reflection, minimizing the bias of interpersonal influence and time pressures.12

ConclusionsThe concept of “stable” HF is not well-recognized among all experts and encourages therapeutic inertia. HF is a progressive disease, even for the patient group theoretically considered “stable”. Treatment optimization should therefore be assessed in each consultation and not postponed until there is a worsening of symptoms. The results of this Delphi study help prepare proposals for improving the care of outpatients with HFrEF.

FundingThe study sponsor was the Research Agency of the Spanish Society of Cardiology, which was given an unconditional grant from Novartis.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank the panelists participating as experts in the Delphi consensus. Without them, it would not have been possible to conduct this study.

Please cite this article as: Barrios V., Escobar C., Ortiz Cortés C., Cosín Sales J., Pascual Figal D.A., García-Moll Marimón X. Manejo de los pacientes con insuficiencia cardiaca atendidos en la consulta de cardiología: Estudio IC-BERG. Rev Clin Esp. 2020;220:339–349.