In patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), the presence of increased waist circumference and triglycerides is a reflection of increased visceral fat and insulin resistance. However, information about the prevalence and clinical characteristics of the hypertriglyceridemic waist (HTGW) phenotype in patients with DM2 is scarce. The aim of the present study was to analyze the prevalence and characteristics of DM2 patients with HTGW.

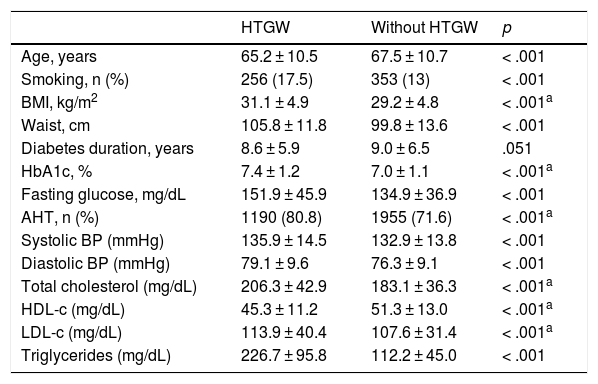

MethodsWe analyzed 4214 patients with DM2 in this epidemiological, cross-sectional study conducted in primary care centers across Spain between 2011 and 2012. The HTGW phenotype was defined as increased waist circumference according to the International Diabetes Federation criteria for Europids (≥ 94 cm for men and ≥ 80 cm for women) with the presence of triglyceride levels ≥ 150 mg/dL. We compared the demographic, clinical and analytical variables according to the presence or absence of the HTGW phenotype.

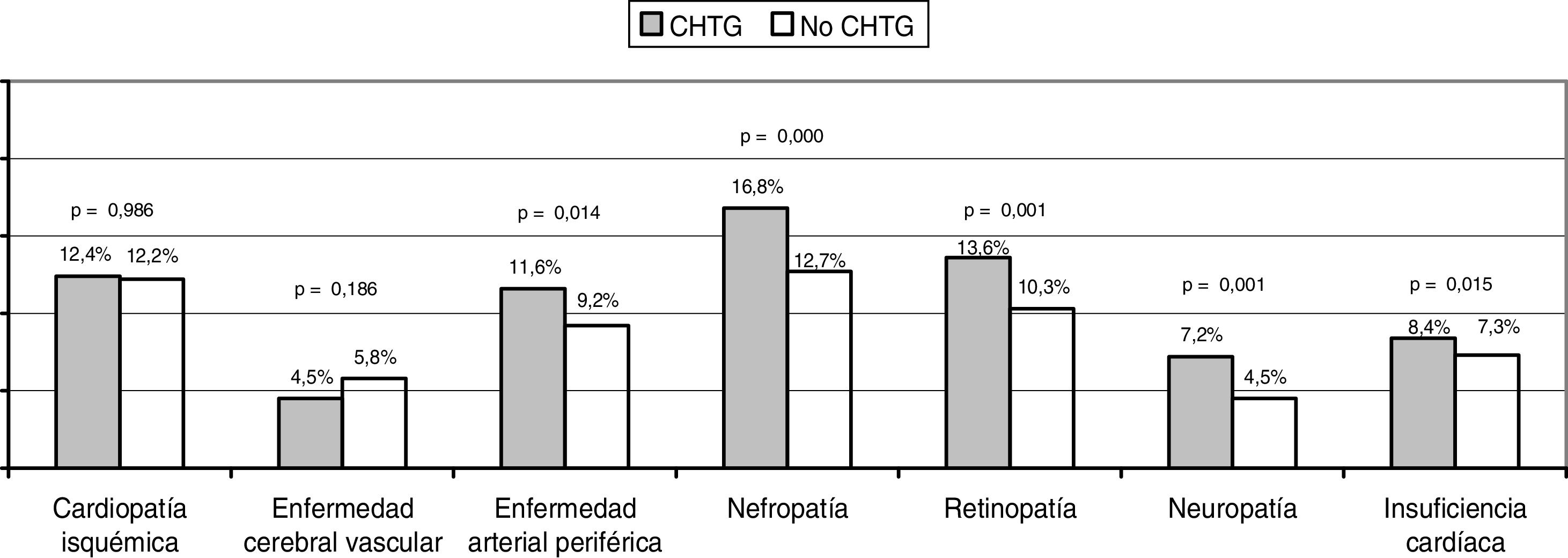

ResultsThirty-five percent of patients presented the HTGW phenotype. Patients with the HTGW phenotype had a higher body mass index (31.14 ± 4.88 vs. 29.2 ± 4.82 kg/m2; p < .001) and glycated hemoglobin levels (7.38 ± 1.2% vs. 7 ± 1.07%; p < .001). The presence of hypertension, peripheral arterial disease, cardiac insufficiency and microvascular complications were higher when compared with patients without the HTGW phenotype. Patients with the HTGW phenotype were less adherent to prescribed diet (69.8 vs. 81%; p < .001), exercise (44.6 vs. 58.2%; p < .001) and presented greater weight increase within the year prior to the study visit (29.4 vs. 22.5%; p < .001).

ConclusionsThe HTGW phenotype is prevalent in the Spanish DM2 population and identifies a subgroup of patients with higher cardiometabolic risk and prevalence of diabetic complications.

En los pacientes con diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (DM2) la presencia de aumento de la circunferencia de la cintura y de los triglicéridos es un reflejo del aumento de la grasa visceral y de la resistencia a la insulina. Sin embargo, es escasa la información acerca de la prevalencia y de las características clínicas del fenotipo de cintura hipertrigliceridémica (CHTG) en pacientes con DM2. El objetivo del presente estudio fue analizar la prevalencia y las características de los pacientes de DM2 con CHTG.

MétodosEn este estudio epidemiológico transversal, llevado a cabo en centros de atención primeria de toda España entre los años 2011 y 2012, analizamos a 4.214 pacientes con DM2. El fenotipo CHTG fue definido como un aumento de la circunferencia de la cintura conforme a los criterios de la Federación Internacional de Diabetes para caucásicos (≥ 94 cm para hombres y ≥ 80 cm para mujeres) acompañado de niveles de triglicéridos ≥ 150 mg/dL. Comparamos las variables demográficas, clínicas y analíticas según la presencia o ausencia del fenotipo CHTG.

ResultadosEl 35% de los pacientes presentaron el fenotipo CHTG. Los pacientes con fenotipo CHTG tenían mayor índice de masa corporal (31,14 ± 4,88 vs. 29,2 ± 4,82 kg/m2; p < 0,001) y hemoglobina glucosilada más alta (7,38±1,2% vs. 7±1,07%; p < 0,001). La presencia de hipertensión, enfermedad arterial periférica, insuficiencia cardíaca y complicaciones microvasculares fueron más frecuentes en los pacientes con fenotipo CHTG que los que no lo tenían. Los pacientes con fenotipo CHTG tenían una menor adherencia a la dieta prescrita (69,8 vs. 81%; p < 0,001), al ejercicio (44,6 vs. 58,2%; p<0,001), y el aumento de peso en el año previo al estudio fue mayor (29,4 vs. 22,5%; p<0,001).

ConclusionesEl fenotipo CHTG es prevalente en la población DM2 española e identifica a un subgrupo de pacientes con un elevado riesgo cardio-metabólico y mayor prevalencia de complicaciones diabéticas.

Article

Diríjase desde aquí a la web de la >>>FESEMI<<< e inicie sesión mediante el formulario que se encuentra en la barra superior, pulsando sobre el candado.

Una vez autentificado, en la misma web de FESEMI, en el menú superior, elija la opción deseada.

>>>FESEMI<<<