Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) is characterized by a combination of intestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms triggered by gluten consumption, without evidence of celiac disease (CD) or wheat allergy (WA). Anemia, as an extra-intestinal manifestation, has been little studied in this context.

Main objectiveTo synthesize the available evidence on the association between NCGS and anemia.

Secondary objectiveTo evaluate studies applying the Salerno criteria as a diagnostic method.

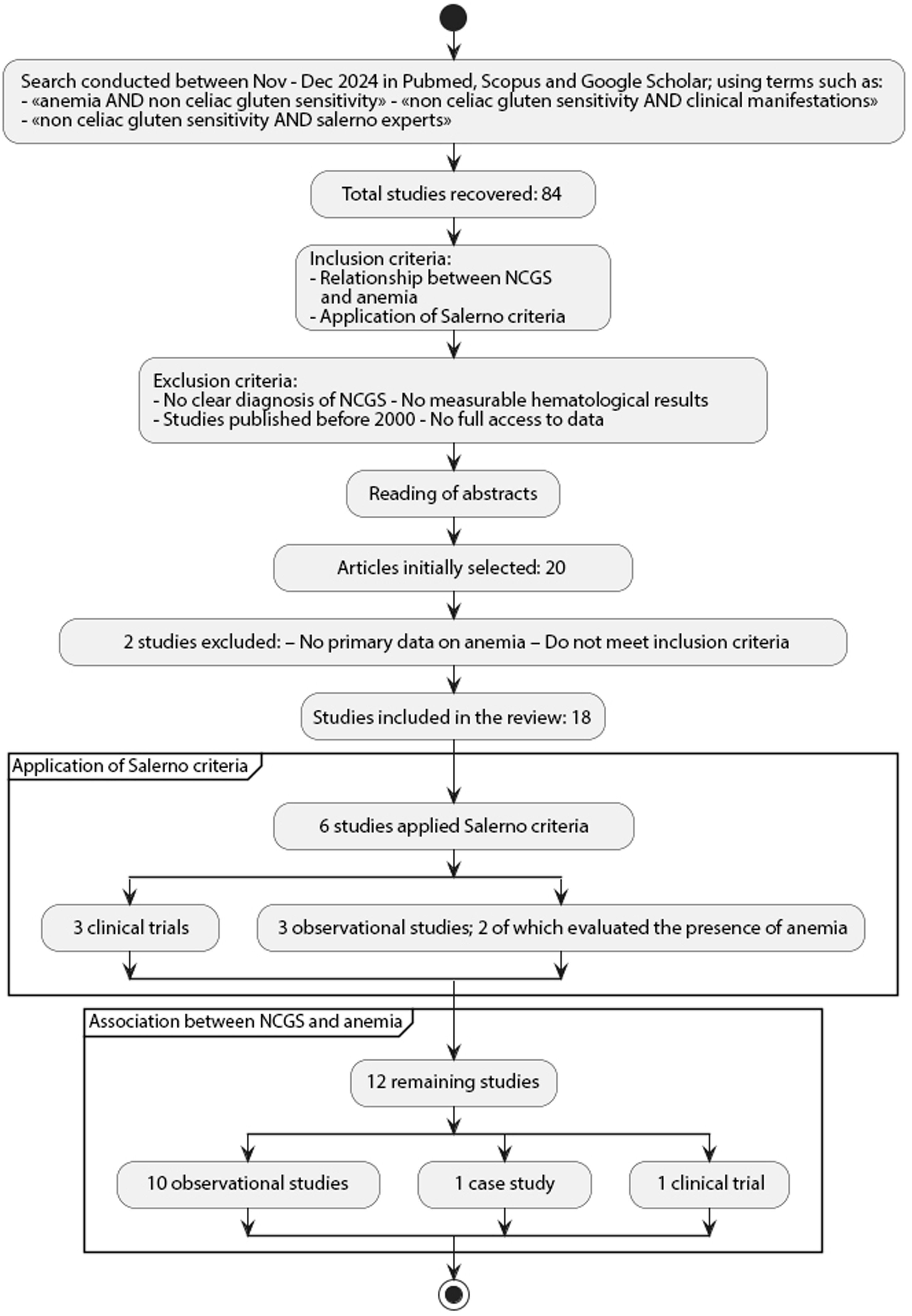

MethodsBetween November and December 2024, a search for scientific articles was conducted in the PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases, using the following terms: “anemia AND non-celiac gluten sensitivity”; “non-celiac gluten sensitivity AND clinical manifestations”; “non-celiac gluten sensitivity AND Salerno Experts.” Studies were included that either reported data on anemia in NCGS and/or used the Salerno criteria for the diagnosis of NCGS. The methodological quality of observational studies was assessed using the STROBE checklist, and the review was structured according to PRISMA 2020.

Results18 studies were selected. The frequency of anemia in patients with NCGS ranged from 15% to 43%. Improvement in hemoglobin levels was reported after a gluten-free diet. Only 6 studies were developed according to the Salerno criteria.

ConclusionsNCGS should be considered in the differential diagnosis of anemia. The methodological quality of studies needs to be improved, ideally through double-blind controlled (DBPC) trials applying the Salerno criteria.

La sensibilidad al gluten no celíaca (SGNC) se caracteriza por una combinación de síntomas intestinales y extraintestinales inducidos por el consumo de gluten, sin evidencia de enfermedad celíaca (EC) ni alergia al trigo (AT). La anemia, como manifestación extraintestinal, ha sido poco estudiada en este contexto.

Objetivo principalSintetizar la evidencia disponible sobre la asociación entre la SGNC y anemia.

Objetivo secundarioEvaluar estudios que aplican los criterios de Salerno como método diagnóstico.

MétodosEntre noviembre y diciembre de 2024, se llevó a cabo una búsqueda de artículos científicos en las base de datos de Pubmed, Scopus y Google Scholar, utilizando los términos siguientes «anemia AND non celiac gluten sensitivity»; «non celiac gluten sensitivity AND clinical manifestations»; «non celiac gluten sensitivity AND Salerno Experts». Se incluyeron por un lado, estudios sobre la SGNC que reportaron datos sobre anemia y por otro lado estudios que utilizaron los criterios de Salerno para el diagnóstico de la SGNC. La calidad metodológica de los estudios observacionales fue evaluada utilizando el cuestionario STROBE y la revisión se estructuró según PRISMA 2020.

ResultadosSe seleccionaron 18 estudios. La frecuencia de anemia en pacientes con SGNC varió entre un 15% y un 43%. Se reportó mejora en los valores de hemoglobina tras una dieta libre de gluten (DLG). Se encontraron solo 6 estudios desarrollados según los criterios de Salerno.

ConclusionesLa SGNC debe considerarse en el diagnóstico diferencial de la anemia. Es necesario mejorar la calidad metodológica de los estudios, idealmente mediante ensayos controlados doble ciego (DBPC) que apliquen los criterios de Salerno.

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) is a syndrome characterized by intestinal and extraintestinal symptoms related to the consumption of food containing gluten, in people without celiac disease (CD) or wheat allergy (WA).1,2 The specific cause has not yet been identified and could include not only gluten, but other components such as amylase-trypsin inhibitors (ATI)3,4 or short-chain fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPs).5–7 Thus, some authors propose a broader term: non-celiac wheat sensitivity (NCWS).8 It has been reported that ATIs activate innate immunity by modifying intestinal permeability through the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) complex expressed by monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells of the intestinal mucosa, promoting intestinal inflammation,9 which suggests a possible involvement of both innate and acquired immunity in the NCGS.10–13 In the absence of specific biomarkers, self-diagnosed wheat/gluten-intolerant patients may be considered as NCGS cases once CD and WA have been ruled out.14 A systematic review in Italy by Losurdo et al. showed that NCGS may have systemic manifestations similar to CD. A prevalence of anemia of between 15% and 23% was reported, though without a control group in many studies, making firm conclusions difficult. In addition, folate deficiency was identified as a common finding and potential predictor of NCGS.15 On the other hand, Lionetti et al. compared 11 clinical trials for the diagnosis of NCGS and found that only 3 applied the Salerno criteria, observing a low prevalence of NCGS after the gluten challenge, but a better classification of real cases with the use of these criteria.16 The objectives of this systematic review were to analyze the relationship between NCGS and anemia, and to evaluate the studies that applied the Salerno criteria for diagnosis.

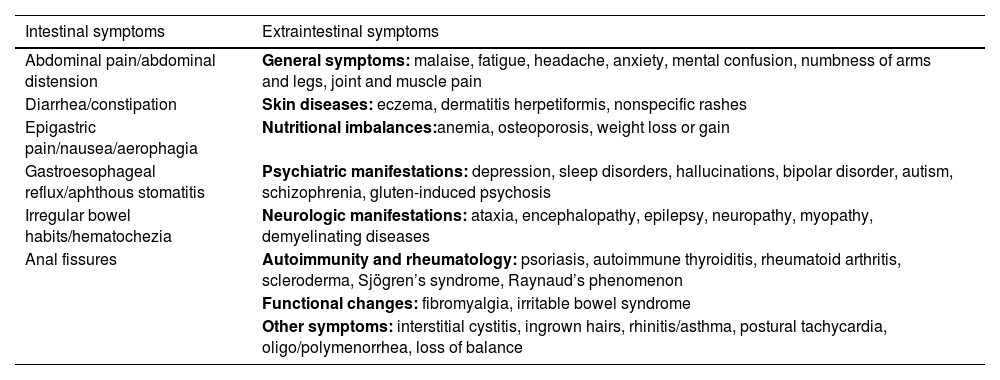

Clinical manifestationsClinical manifestations of NCGS may overlap with other conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), making diagnosis difficult. In a prospective multicenter study conducted by Volta et al.17 at 38 Italian centers, 486 patients with suspected NCGS were evaluated between 2012 and 2013. The symptoms identified included abdominal pain and distension, altered bowel transit (diarrhea or constipation), in addition to multiple extra-gastrointestinal symptoms including iron or folate deficiency anemia (Table 1).

Symptoms described for NCGS.

| Intestinal symptoms | Extraintestinal symptoms |

|---|---|

| Abdominal pain/abdominal distension | General symptoms: malaise, fatigue, headache, anxiety, mental confusion, numbness of arms and legs, joint and muscle pain |

| Diarrhea/constipation | Skin diseases: eczema, dermatitis herpetiformis, nonspecific rashes |

| Epigastric pain/nausea/aerophagia | Nutritional imbalances:anemia, osteoporosis, weight loss or gain |

| Gastroesophageal reflux/aphthous stomatitis | Psychiatric manifestations: depression, sleep disorders, hallucinations, bipolar disorder, autism, schizophrenia, gluten-induced psychosis |

| Irregular bowel habits/hematochezia | Neurologic manifestations: ataxia, encephalopathy, epilepsy, neuropathy, myopathy, demyelinating diseases |

| Anal fissures | Autoimmunity and rheumatology: psoriasis, autoimmune thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, Sjögren’s syndrome, Raynaud’s phenomenon |

| Functional changes: fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome | |

| Other symptoms: interstitial cystitis, ingrown hairs, rhinitis/asthma, postural tachycardia, oligo/polymenorrhea, loss of balance |

Clinically, distinguishing NCGS from CD is complex, but an important difference is the time to onset of symptoms: in NCGS, it usually occurs between a few hours and one day after gluten consumption, while in CD this may take weeks or years.17 Biesiekierski et al.,1 in a clinical trial using a DBPC test in 34 patients with IBS without CD, found that IBS-like symptoms and fatigue, as isolated extraintestinal manifestation, recurred more frequently in the gluten-exposed group than in the placebo group (68% and 40%, respectively). Although IBS-type bowel symptoms are more common in patients with NCGS, they also usually report at least two extraintestinal symptoms, the most common being “brain fog” (feeling of lethargy after eating gluten) (42%) and fatigue (36%).6,18 These results have led some authors to consider that NCGS and IBS could be manifestations of the same disorder.15,19 However, other investigators emphasize that the NCGS shows no systemic symptoms in the IBS.18

Cárdenas-Torres et al.20 highlight key differences between NCGS and IBS. NCGS is triggered by gluten, ATI and FODMAPs, while IBS is not linked to specific components. Clinically, NCGS includes both intestinal and extraintestinal symptoms, while gastrointestinal symptoms predominate in IBS. Its diagnosis is based on a double-blind placebo-controlled (DBPC) trial, unlike IBS, which uses Rome IV criteria. NCGS treatment involves GFD and/or low FODMAPs, while IBS requires a comprehensive approach.

DiagnosisDiagnosis of NCGS should be considered in patients with persistent intestinal symptoms (such as those of IBS) and/or extraintestinal symptoms, in the absence of positive serological markers for CD and WA, which worsen after gluten intake. In 2014, an expert panel meeting in Salerno (Italy) proposed standardized diagnostic criteria in the absence of specific biomarkers. The most reliable method is a DBPC trial, which assesses the response to the elimination and introduction of gluten.3 The patient must identify one to three main symptoms, assessed using a numerical scale from 1 to 10, with a positive response being when there is a 30% change in at least one of these symptoms between phases with gluten and placebo.3,21,22 The protocol includes two phases: an elimination phase (at least six weeks on a GFD), followed by gluten or placebo challenge for one week each, with a one-week gluten-free interval. The gluten preparation should include 8 g daily, at least 0.3 g of ATI and be free of FODMAPs; the placebo should be indistinguishable in texture, taste and nutritional content.3 For a complete diagnostic evaluation, the patient should be eating gluten. If the patient already follows a GFD, only the challenge phase can be performed. In both phases, a self-administered questionnaire based on a modified version of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) is used, which also includes extraintestinal symptoms.23 In clinical practice, evaluating extraintestinal manifestations such as anemia may facilitate the diagnosis of NCGS.14

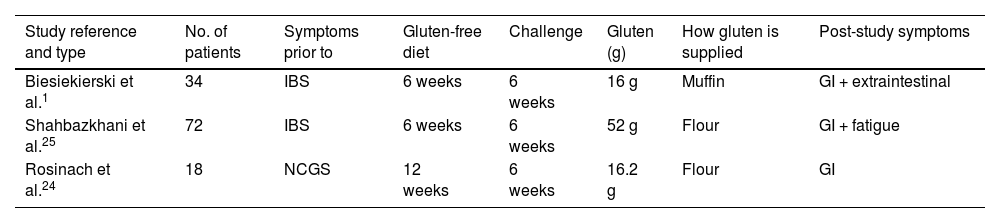

Lionetti et al.,16 in a systematic review of clinical trials to diagnose NCGS, found only three studies that applied the Salerno criteria (Table 2). In these studies, 40% of patients relapsed on gluten versus 24% on placebo (p = 0.003),1,16,24,25 indicating a significant relationship between gluten and the occurrence of symptoms. The relative risk (RR) of relapse with gluten was also significant (2.8; p = 0.002). However, when considering all studies from the review, only 36% of patients relapsed with gluten versus 31% with placebo (p = 0.2; RR = 0.4; p = 0.16), with no statistically significant difference,16,26 In the absence of specific biomarkers, these data support a causal relationship between gluten and recurrent symptoms in NCGS patients when the Salerno criteria are used for diagnosis.16,21,27 However, despite being considered the “gold standard test”, this DBPC provocation test only identifies between 30% and 40% of patients with clinical suspicion of NCGS,16,26 suggesting that it may not capture the full heterogeneity of this condition. Studies such as those by Di Stefano et al., Elli et al. and Zanini et al. showed diagnosis rates after DBPC provocation of only 52%, 14% and 34%, respectively.28–31 However, according to Lionetti et al., these investigations did not strictly apply the Salerno criteria.16 On the other hand, this protocol has not been clinically validated, has a high risk of a nocebo effect (where patients experience symptoms with placebo, due to their negative expecations)1,17,30,32 and does not consider other components of wheat such as FODMAPs or ATIs, which could also cause symptoms in NCGS.33

Examples of studies following the Salerno criteria.

| Study reference and type | No. of patients | Symptoms prior to | Gluten-free diet | Challenge | Gluten (g) | How gluten is supplied | Post-study symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biesiekierski et al.1 | 34 | IBS | 6 weeks | 6 weeks | 16 g | Muffin | GI + extraintestinal |

| Shahbazkhani et al.25 | 72 | IBS | 6 weeks | 6 weeks | 52 g | Flour | GI + fatigue |

| Rosinach et al.24 | 18 | NCGS | 12 weeks | 6 weeks | 16.2 g | Flour | GI |

Several observational studies have shown that NCGS may present immunological and systemic manifestations similar to those of CD. Volta et al.,17 after studying 486 patients with suspected NCGS, found a high association with IBS (47%), a significant prevalence of other food intolerances (1/3 of patients), and IgE-mediated allergies (20%). In addition, a high prevalence of autoimmune diseases such as Hashimoto thyroiditis and psoriasis and a high frequency of nickel allergy (as in CD) were observed. In agreement, Carroccio et al.34 found a higher frequency of anemia, autoimmune disorders, ANA positivity, and HLA-DQ2/DQ8 haplotypes in patients with NCGS or CD as compared to those in the IBS group.

As regards the serological profile, Volta et al.18 found that over 50% of patients with NCGS were positive for anti-gliadin IgG antibodies, but negative for specific CD markers: anti-endomysial antibodies (EmA), tissue transglutaminase (tTGA) or deamidated gliadin peptide antibodies (DGP-AGA). An increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) was observed in 42% (Marsh 1), suggesting a possible mild alteration of the intestinal mucosa. Potential biomarkers for NCGS such as eosinophilic infiltration of the intestinal mucosa, increased CD3+ intraepithelial T cells, presence of mast cells, cytokine profiles, microRNA signatures, and RNA transcription patterns have also been proposed.20,33,35–40

In another study, Carroccio et al.32 analyzed 276 patients with NCWS, identifying two clinical subgroups, one with only NCWS and one with multiple food hypersensitivity. Both groups had a higher frequency of anemia, self-reported wheat intolerance, atopy, and childhood food allergies than the IBS group. In addition, patients with NCWS had eosinophilic infiltration of the intestinal mucosa and a high frequency of anti-gliadin antibodies and basophil activation in vitro. Those with only NCWS showed a similar clinical profile to that of CD, while those with multiple food sensitivity more closely resembled allergic patients. Approximately 50% have HLA-DQ2/DQ8 haplotypes.41

Finally, Cárdenas-Torres et al. and Roszkowska et al.20,42 compared NCGS, CD, and WA, showing that CD is an autoimmune disease with specific markers and intestinal atrophy (Marsh I–IV); NCGS, in contrast, involves innate immunity and mild lesions (Marsh 0–II); while WA is a mediated IgE reaction. Both NCGS and WA may present extraintestinal symptoms, but their diagnosis requires different approaches and does not present the immunological or histological markers characteristic of CD. Although the Salerno protocol represents the most rigorous method for the diagnosis of NCGS, its clinical applicability is limited, and diagnosis should therefore be supported by a comprehensive evaluation including gastrointestinal symptoms, systemic symptoms, and investigations.

Materials and methodsThis study corresponds to a critical analysis of the selected registries through a systematic review, developed following the guidelines of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guide.43 The search was performed between November and December 2024 in the PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar databases, using terms like “anemia AND non celiac gluten sensitivity”, “non celiac gluten sensitivity AND clinical manifestations”, and “non celiac gluten sensitivity AND Salerno Experts”.

Studies explicitly addressing the relationship between NCGS and anemia and/or studies clearly applying the Salerno criteria for diagnosis of NCGS were included. Studies with no clear diagnosis of NCGS, no measurable hematological results, prior to 2000, or no complete access to data were excluded. Of a total of 84 studies retrieved, after reading the summaries and applying the abovementioned criteria, 20 articles were initially selected, of which 2 were excluded because they did not contain primary data on anemia or did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, 18 studies were included in the review (Fig. 1). Data extracted included: year, country, type of study, number of patients, presence of anemia, application of NCGS diagnostic criteria, and clinical outcomes after a GFD.

The primary variables of interest were: 1. prevalence of anemia in patients with NCGS, and 2. clinical response to a GFD together with the application of standardized diagnostic criteria. Due to the methodological and clinical heterogeneity of the studies, no meta-analyses were performed, and no formal heterogeneity analyses or sensitivity analyses were applied by type of study. Instead, a comparative narrative analysis was chosen (Table 3).

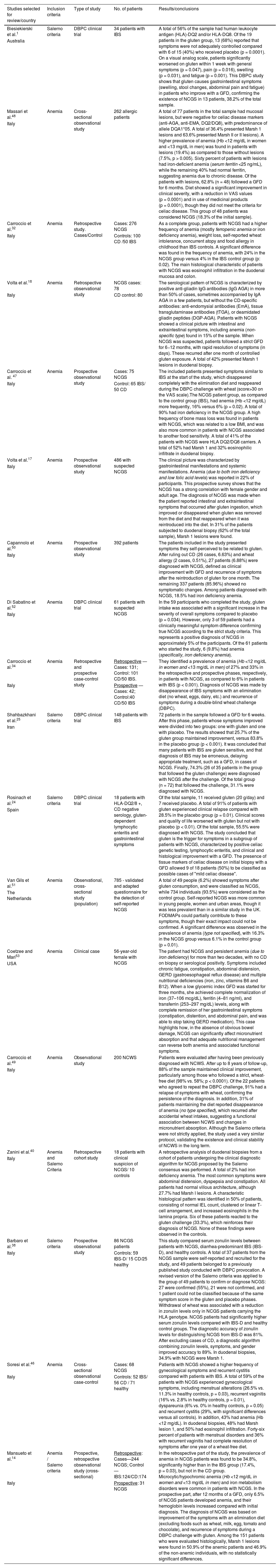

Description of the studies included in the review.

| Studies selected for review/country | Inclusion criteria | Type of study | No. of patients | Results/conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biesiekierski et al.1 | Salerno criteria | DBPC clinical trial | 34 patients with IBS | A total of 56% of the sample had human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DQ2 and/or HLA-DQ8. Of the 19 patients in the gluten group, 13 (68%) reported that symptoms were not adequately controlled compared with 6 of 15 (40%) who received placebo (p = 0.0001). On a visual analog scale, patients significantly worsened on gluten within 1 week with general symptoms (p = 0.047), pain (p = 0.016), swelling (p = 0.031), and fatigue (p = 0.001). This DBPC study shows that gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms (swelling, stool changes, abdominal pain and fatigue) in patients who improve with a GFD, confirming the existence of NCGS in 13 patients, 38.2% of the total sample. |

| Australia | ||||

| Massari et al.48 | Anemia | Cross-sectional observational study | 262 allergic patients | A total of 77 patients in the total sample had mucosal lesions, but were negative for celiac disease markers (anti-AGA, anti-EMA, DQ2/DQ8), with predominance of allele DQA1*05. A total of 36.4% presented Marsh 1 lesions and 63.6% presented Marsh II or II lesions). A higher prevalence of anemia (Hb <12 mg/dL in women and <13 mg/dL in men) was found in patients with lesions (19.4%) as compared to those without lesions (7.5%, p > 0.005). Sixty percent of patients with lesions had iron-deficient anemia (serum ferritin <25 ng/mL), while the remaining 40% had normal ferritin, suggesting anemia due to chronic disease. Of the patients with lesions, 62.8% (n = 48) followed a GFD for 6 months. Diet showed a significant improvement in clinical severity, with a reduction in VAS values (p = 0.0001) and in use of medicinal products (p = 0.0001), though they did not meet the criteria for celiac disease. This group of 48 patients was considered NCGS (18.3% of the initial sample). |

| Italy | ||||

| Carroccio et al.32 | Anemia | Retrospective study. Cases/Control | Cases: 276 NCGS | As a complete group, patients with NCGS had a higher frequency of anemia (mostly ferropenic anemia or iron deficiency anemia), weight loss, self-reported wheat intolerance, concurrent atopy and food allergy in childhood than IBS controls. A significant difference was found in the frequency of anemia, with 24% in the NCGS group versus 4% in the IBS control group (p: 0.02). The main histological characteristic of patients with NCGS was eosinophil infiltration in the duodenal mucosa and colon. |

| Italy | Controls: 100 CD /50 IBS | |||

| Volta et al.18 | Anemia | Retrospective observational study | NCGS cases: 78 | The serological pattern of NCGS is characterized by positive anti-gliadin IgG antibodies (IgG AGA) in more than 50% of cases, sometimes accompanied by IgA AGA in a few patients, but without the CD-specific antibodies: anti-endomysial antibodies (EmA), tissue transglutaminase antibodies (tTGA), or deamidated gliadin peptides (DGP-AGA). Patients with NCGS showed a clinical picture with intestinal and extraintestinal symptoms, including anemia (non-specific type) found in 15% of the sample. When NCGS was suspected, patients followed a strict GFD for 6−12 months, with rapid resolution of symptoms (in days). These recurred after one month of controlled gluten exposure. A total of 42% presented Marsh 1 lesions in duodenal biopsy. |

| Italy | CD control: 80 | |||

| Carroccio et al. 47 | Anemia | Prospective observational study | Cases: 75 NCGS | The included patients presented symptoms similar to IBS at the start of the study, which disappeared completely with the elimination diet and reappeared during the DBPC challenge with wheat (score>30 on the VAS scale).The NCGS patient group, as compared to the control group (IBS), had anemia (Hb <12 mg/dL) more frequently, 16% versus 6% (p = 0.02). A total of 90% had iron deficiency in the NCGS group. A high frequency of bone mass loss was found in patients with NCGS, which was related to a low BMI, and was also more common in patients with NCGS associated to another food sensitivity. A total of 41% of the patients with NCGS were HLA DQ2/DQ8 carriers. A total of 52% had Marsh 1 and 32% eosinophilic infiltrate in duodenal biopsy. |

| Italy | ||||

| Control: 65 IBS/ 50 CD | ||||

| Volta et al.17 | Anemia | Prospective observational study | 486 with suspected NCGS | The clinical picture was characterized by gastrointestinal manifestations and systemic manifestations. Anemia (due to both iron deficiency and low folic acid levels) was reported in 22% of participants. This prospective survey shows that the NCGS has a strong correlation with female gender and adult age. The diagnosis of NCGS was made when the patient reported intestinal and extraintestinal symptoms that occurred after gluten ingestion, which improved or disappeared when gluten was removed from the diet and that reappeared when it was reintroduced into the diet. In 31% of the patients subjected to duodenal biopsy (62% of the total sample), Marsh 1 lesions were found. |

| Italy | ||||

| Capannolo et al.50 | Anemia | Prospective observational study | 392 patients | The patients included in the study presented symptoms they self-perceived to be related to gluten. After ruling out CD (26 cases, 6.63%) and wheat allergy (2 cases, 0.51%), 27 patients (6.88%) were diagnosed with NCGS, defined as clinical improvement with GFD and recurrence of symptoms after the reintroduction of gluten for one month. The remaining 337 patients (85.96%) showed no symptomatic changes. Among patients diagnosed with NCGS, 18.5% had iron deficiency anemia. |

| Italy | ||||

| Di Sabatino et al.52 | Anemia | DBPC clinical trial | 61 patients with suspected NCGS | In the 59 participants who completed the study, gluten intake was associated with a significant increase in the severity of overall symptoms compared to placebo (p = 0.034). However, only 3 of 59 patients had a clinically meaningful symptom difference confirming true NCGS according to the strict study criteria. This represents a positive diagnosis of NCGS in approximately 5% of the participants. Of the 61 patients who started the study, 6 (9.8%) had anemia (specifically, iron deficiency anemia). |

| Italy | ||||

| Carroccio et al.34 | Anemia | Retrospective and prospective case-control study | Retrospective — Cases: 131; Control: 101 CD/50 IBS. | They identified a prevalence of anemia (Hb <12 mg/dL in women and <13 mg/dL in men) of 27% and 33% in the retrospective and prospective phases, respectively, in patients with NCGS, as compared to 6% in patients with IBS (p < 0.001). Diagnosis of NCGS was made by disappearance of IBS symptoms with an elimination diet (no wheat, eggs, dairy, etc.) and recurrence of symptoms during a double-blind wheat challenge (DBPC). |

| Italy | Prospective — Cases: 42; Control:40 CD/50 IBS | |||

| Shahbazkhani et al.25 | Salerno criteria | DBPC clinical trial | 148 patients with IBS | 72 patients in the sample followed a GFD for 6 weeks. After this phase, patients whose symptoms improved were divided into two groups: one with gluten and one with placebo. The results showed that 25.7% of the gluten group maintained improvement, versus 83.8% in the placebo group (p < 0.001). It was concluded that many patients with IBS are gluten sensitive, and that diagnosis of IBS may be erroneous, delaying appropriate treatment, such as a GFD, in cases of NCGS. Finally, 74.3% (26 of 35 patients in the group that followed the gluten challenge) were diagnosed with NCGS after the challenge. Of the total group (n = 72) that followed the challenge, 31.1% were diagnosed with NCGS. |

| Iran | ||||

| Rosinach et al.24 | Salerno criteria | DBPC clinical trial | 18 patients with HLA-DQ2/8 +, CD negative serology, gluten-dependent lymphocytic enteritis and gastrointestinal symptoms | Of the total sample, 11 received gluten (20 g/day) and 7 received placebo. A total of 91% of patients with gluten experienced clinical relapse compared with 28.5% in the placebo group (p = 0.01). Clinical scores and quality of life worsened with gluten but not with placebo (p < 0.01). Of the total sample, 55.5% were diagnosed with NCGS. The study concluded that gluten is the trigger for symptoms in a subgroup of patients with NCGS, characterized by positive celiac genetic testing, lymphocytic enteritis, and clinical and histological improvement with a GFD. The presence of tissue markers of celiac disease on initial biopsy with a GFD allowed 9 of 18 patients (50%) to be classified as possible cases of "mild celiac disease". |

| Spain | ||||

| Van Gils et al.51 | Anemia | Observational, cross-sectional study (population) | 785 - validated and adapted questionnaire for the detection of self-reported NCGS | A total of 49 people (6.2%) showed symptoms after gluten consumption, and were classified as NCGS, while 734 individuals (93.5%) were considered as the control group. Self-reported NCGS was more common in young people, women and urban areas, though it was less prevalent than in a similar study in the UK. FODMAPs could partially contribute to these symptoms, though their exact impact could not be confirmed. A significant difference was observed in the prevalence of anemia (type not specified), with 16.3% in the NCGS group versus 6.1% in the control group (p = 0.01). |

| The Netherlands | ||||

| Coetzee and Mari53 | Anemia | Clinical case | 56-year-old female with NCGS | The patient had NCGS and persistent anemia (due to iron deficiency) for more than two decades, with no CD on biopsy or serological positivity. Symptoms included chronic fatigue, constipation, abdominal distension, GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease) and multiple nutritional deficiencies (iron, zinc, vitamins B6 and B12). When a low glycemic index GFD was started for three months, she achieved complete normalization of iron (37–106 mcg/dL), ferritin (4–81 ng/ml), and transferrin (253–297 mg/dL) levels, along with complete remission of her gastrointestinal symptoms (constipation, distention, and abdominal pain, and was able to stop taking GERD medication). This case highlights how, in the absence of obvious bowel damage, NCGS can significantly affect micronutrient absorption and that adequate nutritional management can reverse both anemia and associated functional symptoms. |

| USA | ||||

| Carroccio et al.49 | Anemia | Observational study | 200 NCWS | Patients were evaluated after having been previously diagnosed with NCWS. After up to 8 years of follow-up, 88% of the sample maintained clinical improvement, particularly among those who followed a strict, wheat-free diet (98% vs. 58%; p < 0.0001). Of the 22 patients who agreed to repeat the DBPC challenge, 91% had a relapse of symptoms with wheat, confirming the persistence of the diagnosis. In addition, 31% of patients maintaining the diet reported disappearance of anemia (no type specified), which recurred after accidental wheat intakes, suggesting a functional association between NCWS and changes in micronutrient absorption. Although the Salerno criteria were not strictly applied, the study used a very similar protocol, validating the existence and clinical stability of NCWS in the long term. |

| Italy | ||||

| Zanini et al.40 | Anemia and Salerno Criteria | Retrospective cohort study | 18 patients with clinical suspicion of NCGS/ 10 controls | A retrospective analysis of duodenal biopsies from a cohort of patients undergoing the clinical diagnostic algorithm for NCGS proposed by the Salerno consensus was performed. A total of 2% had iron deficiency anemia. The most common symptoms were abdominal distension, dyspepsia and constipation. All patients had normal villous architecture, although 27.7% had Marsh I lesions. A characteristic histological pattern was identified in 50% of patients, consisting of normal IEL count, clustered or linear T-cell arrangement, and increased eosinophils in the lamina propria. Six of these patients reacted to the gluten challenge (33.3%), which reinforces their diagnosis of NCGS. None of these findings were observed in the controls. |

| Italy | ||||

| Barbaro et al.38 | Salerno criteria | Prospective observational study | 86 NCGS patients | This study compared serum zonulin levels between patients with NCGS, diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D), and healthy controls. A total of 37 patients from the NCGS sample were self-reported and recruited for the study, and 49 patients belonged to a previously published study conducted with DBPC provocation. A revised version of the Salerno criteria was applied to the group of 49 patients to confirm or diagnose NCGS: 27 were confirmed (55%), 21 were not confirmed, and 1 patient could not be classified because of the same symptom score in the gluten and placebo phases. Withdrawal of wheat was associated with a reduction in zonulin levels only in NCGS patients carrying the HLA genotype. NCGS patients had significantly higher serum zonulin levels compared with IBS-D and healthy control groups. The diagnostic accuracy of zonulin levels for distinguishing NCGS from IBS-D was 81%. After excluding cases of CD, a diagnostic algorithm combining zonulin levels, symptoms, and gender improved accuracy to 89%. In duodenal biopsies, 34.9% with NCGS were Marsh 1. |

| Italy | Controls: 59 IBS-D/ 15 CD/25 healthy | |||

| Soresi et al.46 | Anemia | Cross-sectional observational case-control | Cases: 68 NCGS | Patients with NCGS showed a higher frequency of gynecological symptoms and recurrent cystitis compared with patients with IBS. A total of 59% of the patients with NCGS experienced gynecological symptoms, including menstrual alterations (26.5% vs. 11.3% in healthy controls, p = 0.03), recurrent vaginitis (16% vs. 2.8% in healthy controls, p = 0.01), dyspareunia (6% vs. 0% in healthy controls, p = 0.05) and recurrent cystitis (29%, with significant differences versus all controls). In addition, 43% had anemia (Hb <12 mg/dL). In duodenal biopsies, 48% had Marsh lesion 1, and 50% had eosinophil infiltration. Forty-six percent of patients with menstrual disorders and 36% with recurrent vaginitis had complete resolution of symptoms after one year of a wheat-free diet. |

| Italy | Controls: 52 IBS/ 56 CD / 71 healthy | |||

| Mansueto et al.14 | Anemia / Salerno criteria | Prospective, retrospective observational study (cross-sectional) | Retrospective: Cases—244 NCGS; Control—IBS:124/CD:174 | In the retrospective part of the study, the prevalence of anemia in NCGS patients was found to be 34.8%, significantly higher than in the IBS group (17.4%, p = 0.03), but not in the CD group. Microcytic/hypochromic anemia (Hb <12 mg/dL in women and <13 mg/dL in men) and iron metabolism disorders were common in patients with NCGS. In the prospective part, after 12 months of a GFD, only 6.5% of NCGS patients developed anemia, and their hemoglobin levels increased compared with initial diagnosis. The diagnosis of NCGS was based on improvement of the symptoms with an elimination diet (excluding foods such as wheat, milk, egg, tomato and chocolate), and recurrence of symptoms during a DBPC challenge with gluten. Among the 151 patients who were evaluated histologically, Marsh 1 lesions were found in 50.9% of the anemic patients and 46.9% of the non-anemic individuals, with no statistically significant differences. |

| Italy | Prospective: 31 NCGS |

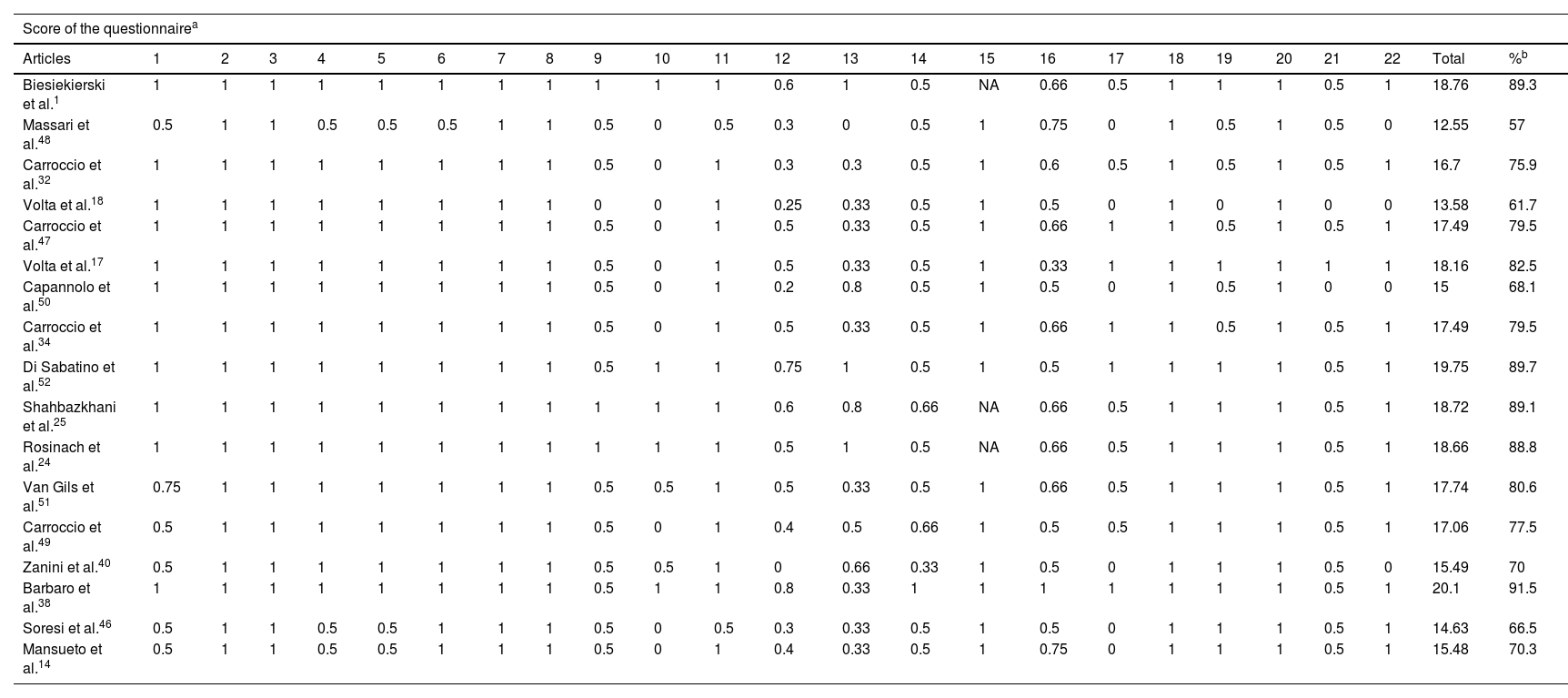

For the evaluation of methodological quality, the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology)44 list was used to assess observational studies (Table 4), yielding a mean compliance of 77.5%. In addition, the CARE list (CAse REport guidelines)45 was applied for the evaluation of the included case report, which showed a compliance level of 51%. These results reflect an acceptable methodological quality in most studies, but with room for improvement in standardization and quality of the clinical and hematological information reported.

Evaluation of articles included in the study using the STROBE questionnaire.

| Score of the questionnairea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | Total | %b |

| Biesiekierski et al.1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.5 | NA | 0.66 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 18.76 | 89.3 |

| Massari et al.48 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.75 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 12.55 | 57 |

| Carroccio et al.32 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 16.7 | 75.9 |

| Volta et al.18 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 13.58 | 61.7 |

| Carroccio et al.47 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.66 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 17.49 | 79.5 |

| Volta et al.17 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.33 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 18.16 | 82.5 |

| Capannolo et al.50 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 68.1 |

| Carroccio et al.34 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.66 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 17.49 | 79.5 |

| Di Sabatino et al.52 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 19.75 | 89.7 |

| Shahbazkhani et al.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.66 | NA | 0.66 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 18.72 | 89.1 |

| Rosinach et al.24 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | NA | 0.66 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 18.66 | 88.8 |

| Van Gils et al.51 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.66 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 17.74 | 80.6 |

| Carroccio et al.49 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.66 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 17.06 | 77.5 |

| Zanini et al.40 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 0.66 | 0.33 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 15.49 | 70 |

| Barbaro et al.38 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.8 | 0.33 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 20.1 | 91.5 |

| Soresi et al.46 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 14.63 | 66.5 |

| Mansueto et al.14 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.75 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 15.48 | 70.3 |

After analysis of the 18 selected studies, 6 studies applying the Salerno criteria for diagnosis of NCGS were found (3 clinical trials and 3 observational studies, two observational studies also evaluated the presence of anemia in patients with NCGS), with diagnostic rates ranging from 38% to 55.5%. The remaining 12 studies found an association between NCGS and anemia, consisting of 10 observational studies, one case study and one clinical trial. The research was conducted in various countries, including Italy, Spain, the United States, the Netherlands, Iran and Australia. Anemia in patients with NCGS, particularly ferropenic anemia, is a common manifestation, its prevalence ranged from 15% to 43%, and is consistently higher than in patients with IBS. The most commonly observed hematological characteristics were microcytic and hypochromic anemia, alterations in iron metabolism and, in some cases, folate deficiency. This could be associated with mild inflammation of the intestinal mucosa (10 studies identified Marsh 1 lesions and/or eosinophilic infiltration) or an impaired iron absorption, even in the absence of the structural damage typical of celiac disease. Two of the studies showed significant clinical improvements after implementation of a GFD, with recovery of hemoglobin levels and resolution of anemia in most cases. Variability in diagnostic methods, assessment of anemia, and overall methodological quality limited the possibility of conducting a meta-analysis and decreased the strength of the evidence collected. Rigorous implementation of the Salerno criteria would allow better identification of the true NCGS phenotype and could establish anemia as a useful clinical marker, though further controlled studies with follow-up and standardized methodologies are needed to confirm this relationship.

DiscussionSalerno criteriaStudies that used the Salerno criteria to diagnose NCGS showed variability in diagnosis rates after the DBPC provocation test, as determined by the design and population included. Rosinach et al. reported the highest rate (91%) in the group that ingested gluten (55.5% of the total sample). Shahbazkhani et al., with a sample of patients initially diagnosed with IBS, found a rate of 74.3% in the gluten group (31.1% of the total sample), while Biesiekierski et al. reported 68% in the gluten group (38.2% of the total sample). In the observational study by Barbaro et al., the diagnosis was confirmed in 55.1% of the 49 patients evaluated retrospectively under a modified version of the Salerno criteria. Finally, Mansueto et al. and Zanini et al. also used these criteria in previous stages to select their patients, also showing an association between anemia and NCGS.1,14,24,25,38,40

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) and AnemiaOverall, the included studies exploring the prevalence of anemia in patients with NCGS show a relevant but poorly recognized clinical association. This may be associated with mild inflammation of the small intestine (intraepithelial lymphocytosis — Marsh 1)14,17,18,38,40,46–48 or by eosinophilic infiltration.32,40,46,47 Or due to impaired iron absorption, even in the absence of the structural damage typical of CD. In general, these studies agree that anemia is more common in patients with NCGS than in those with IBS, and in some cases comparable to that seen in CD.

Studies with a strong association between NCGS and anemia (>30%)Although several authors have documented the presence of anemia in patients with NCGS,17,18,32,34,40,46–53 the most detailed study on its frequency, clinical and biochemical characteristics was conducted by Mansueto et al.,14 where they reported a prevalence of anemia (Hb <12 mg/dL in women and <13 mg/dL in men) of 34.8% in the retrospective phase of their study, a significantly higher percentage than in the IBS group (17.4%, p = 0.03), though lower than in CD. This prevalence decreased to 6.5% after 12 months of GFD in the prospective phase. In addition, Hb levels increased by 2.4 g/dL (after 20 months with GFD), indicating a strong clinical association and possibility of reversal by dietary intervention. Improvement was also seen in microcytic, hypochromic, anisocytosis, and iron metabolism parameters. This study applied the Salerno criteria. Among the patients who were evaluated histologically, 61.8% of the total sample (n = 151) found Marsh 1 lesions in 50.9% of the anemic patients and in 46.9% of the non-anemic patients, with no statistically significant differences. A possible mild intestinal malabsorption is suggested, given the high frequency of duodenal lymphocytosis.

On the other hand, Carroccio et al.34 identified a prevalence of anemia (Hb <12 mg/dL in women and <13 mg/dL in men) of 27% and 33% in the retrospective and prospective phases, respectively, in patients with NCGS, as compared to 6% in patients with IBS (p < 0.001); the study also showed remission of symptoms after elimination diet and DBPC provocation.

In a long-term follow-up, Carroccio et al.49 found that 31% of NCGS patients reported disappearance of anemia with a GFD, which recurred after accidental exposure to wheat, suggesting a strong dietary causal relationship, though the type of anemia was not specified.

Finally, Soresi et al.46 found in a cross-sectional study that 43% of patients with NCGS had anemia (Hb <12 mg/dL), associated to gynecological symptoms that improved with a wheat-free diet, indicating the potential implication of several mechanisms such as malabsorption, losses, or chronic inflammation, despite not having applied a DBPC design. In duodenal biopsies, 48% had Marsh 1 lesions, and 50% had eosinophil infiltration.

Studies with moderate or isolated association (15–24%)Carroccio et al.32 reported a 24% prevalence of anemia in patients with NCGS as compared to 4% in those with IBS (p = 0.02), most of which were iron deficiency anemia. The main histological characteristic of patients with NCGS was eosinophil infiltration in the duodenal and colon mucosa. Subsequently, Carroccio et al.,47 in a prospective study, found anemia (Hb <12 mg/dL) in 16% of patients with NCGS versus 6% in IBS (p = 0.02), and 90% of anemic patients had iron deficiency. A total of 52% had Marsh 1 and 32% eosinophilic infiltrate in duodenal biopsy.

In parallel, Volta et al.17 found a 22% prevalence of anemia in NCGS, attributed to iron or folate deficiency. These changes, less severe than in CD, could be associated to mild inflammation of the small intestine,17,18,54 since in 31% of patients undergoing duodenal biopsy (62% of the total sample), Marsh 1 lesions were found. However, this study did not apply a DBPC provocation test or Salerno criteria, which limits the diagnostic correlation between biochemical changes and histological findings. Similarly, Volta et al.18 documented anemia in 15% of patients with NCGS, without specifying the type, with normal or mildly abnormal intestinal mucosa (42% had an increase in the number of intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) — Marsh 1 in duodenal biopsy).

Capannolo et al.50 reported an 18.5% prevalence of iron deficiency anemia in 27 patients diagnosed with NCGS, supporting the association, but in a reduced sample. Finally, Van Gils et al.,51 in a self-reported cohort assessed using a validated questionnaire, found a prevalence of anemia of 16.3% in the NCGS group versus 6.1% in controls (p = 0.01); though the type of anemia was not specified, this was a population-based study, which supports the association even outside the clinical setting.

Studies with limited but relevant dataIn Massari et al.,48 29.3% of the sample showed duodenal lesions (36.4% Marsh 1 lesions and 63.6% Marsh II or III lesions). The prevalence of anemia (Hb <12 mg/dL in women and <13 mg/dL in men) was 11.1% and it was higher in patients with mucosal lesions than in those without lesions (19.4% versus 7.5%; p > 0.005). Most of the patients with lesions (60%) had iron-deficiency anemia. Of the patients with lesions, 62.3% followed a GFD for 6 months, after which they showed a significant clinical improvement, and were considered as NCGS. The authors proposed the term NCGSE (non-celiac gluten-sensitive enteropathy) for this condition. Di Sabatino et al.,52 in a DBPC clinical trial, found iron deficiency anemia in 9.8% of patients with suspected NCGS, reinforcing the presence of hematological changes in this group. Zanini et al.,40 reported a low prevalence of anemia (2%) (Hb <12 mg/dL) but 27.7% of Marsh type I intraepithelial lymphocytosis, suggesting an immune activation that could interfere with nutrient absorption. Finally, Coetzee and Mari53 described a clinical case of ferropenic anemia diagnosed long ago in a patient with NCGS, which completely resolved after 3 months on a GFD, which shows the positive impact of dietary management even without evident intestinal damage.

Further research on the relationship between NCGS and anemia would be needed because, although its epidemiology is not clearly defined, NCGS is estimated to have a prevalence 6–15 times higher than that of CD.2,6,18,20,41,55

Study limitationsThis study highlights a significant heterogeneity in the definition and evaluation of anemia among the studies included. Although many studies use the hemoglobin threshold of <12 g/dL as the criterion, others do not specify or differentiate between types of anemia. In addition, there is variation in the hematological markers used, from hemoglobin only to ferritin, serum iron, transferrin, folate or vitamin B12. This lack of standardization, together with the methodological diversity of the studies (retrospective, prospective, clinical trials with or without control group), makes comparison of results difficult and excludes the possibility of performing a meta-analysis. There was also a predominance of European studies, especially Italian studies, which limits the generalisation of the findings. Only 6 of 18 studies applied the Salerno diagnostic criteria, and several lacked a control group, and selection and publication bias may be present, with an under-representation of studies with negative results.

ConclusionsNCGS is considered more of a syndrome than a gastrointestinal disease, as it shows symptoms similar to IBS and extraintestinal manifestations that improve with GFD and recur after rechallenge. Literature suggests that NCGS may have systemic involvement comparable to that of CD. This systematic review provides a critically and methodologically robust synthesis of the association between anemia and NCGS, with prevalences ranging from 15% and 43% according to the design and diagnostic criteria applied. It was found that in these patients, a GFD can reduce the prevalence of anemia and improve iron metabolism. Thus, the findings support the inclusion of NCGS in the differential diagnosis of anemia, especially in patients with functional gastrointestinal symptoms. Standardization of the diagnostic criteria for anemia is recommended in future research addressing NCGS as the underlying cause, to improve the comparability and quality of the evidence, and to promote the standardized use of studies with high-quality DBPC designs, in accordance with the Salerno criteria, since their use may improve the diagnosis of the NCGS.

Financial supportThere was no external funding.

The author declares that she has no conflicts of interest.