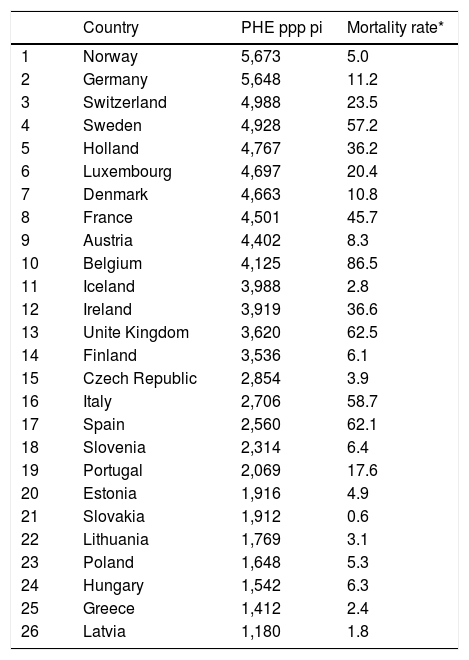

To analyze the association between public health expenditure per capita and the mortality rate due to COVID-19 in Europe and Spain.

Material and methodsPearson's correlation coefficient was used to compare and contrast the mortality rate due to COVID-19 between countries and autonomous communities with higher and lower public health expenditure per capita than the mean.

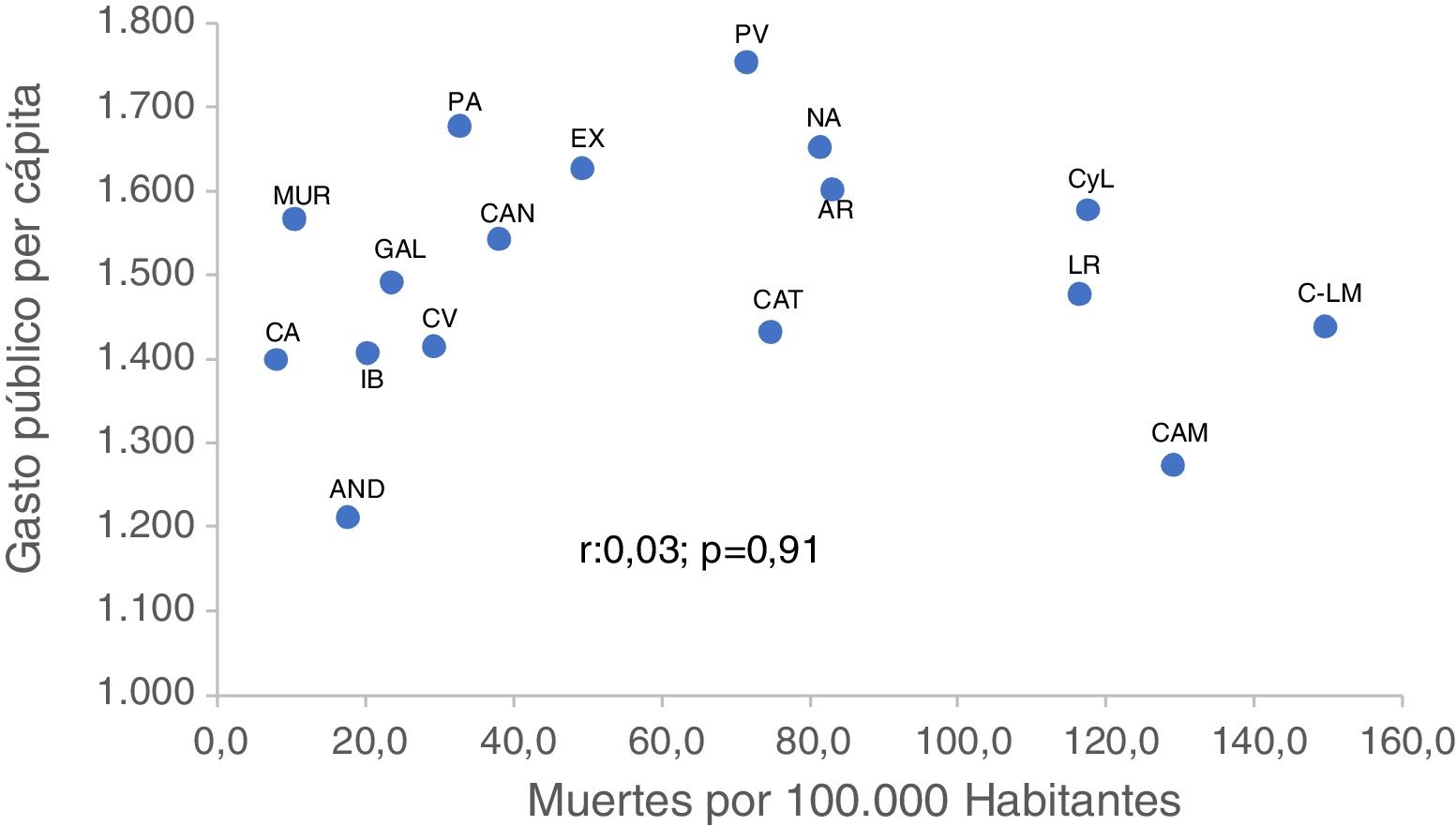

ResultsNo correlation between the public health expenditure per capita and the mortality rate due to COVID-19 (r: 0.3; p = 0.14) was found among European countries or Spain’s Autonomous Communities (r: 0.03; p = 0.91). No significant differences were found when comparing the mortality rate due to COVID-19 among the public health expenditure per capita groups.

ConclusionsThe available evidence does not support association between «low» public healthcare expenditure and the poor outcomes observed in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic. Increased funding for the Spanish National Health System should be earmarked for structural reforms to increase its social efficiency.

Analizar la asociación entre el gasto sanitario público per cápita y la tasa de mortalidad poblacional por COVID-19 en Europa y en España.

Material y métodosSe utilizó el coeficiente de correlación de Pearson. Asimismo, se contrastaron los promedios de TMP-COVID-19 entre países y comunidades autónomas con mayor y menor GSPpc que el promedio.

ResultadosNo se halló correlación, en los países europeos, entre el gasto sanitario público per cápita y la tasa de mortalidad poblacional por COVID-19 (r: 0,3; p = 0,14), ni en las comunidades autónomas (r: 0,03; p = 0,91). Tampoco se encontraron diferencias significativas en el contraste de la tasa de mortalidad poblacional por COVID-19 por grupos de gasto sanitario público per capita.

ConclusionesLa asociación entre «bajo» gasto sanitario público y malos resultados en España en la crisis de la COVID-19 no está sustentada en la evidencia disponible. Los aumentos de financiación de la sanidad pública deberían destinarse a las reformas estructurales para aumentar su eficiencia social.

Article

Diríjase desde aquí a la web de la >>>FESEMI<<< e inicie sesión mediante el formulario que se encuentra en la barra superior, pulsando sobre el candado.

Una vez autentificado, en la misma web de FESEMI, en el menú superior, elija la opción deseada.

>>>FESEMI<<<