Neither the past nor the future exists. Everything is the present.

A few months ago, a working group from the Spanish Society of Internal Medicine (SEMI, for its initials in Spanish), in collaboration with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Foundation (IMAS, for its initials in Spanish), reflected on the characteristics that the “hospital of the future” should have in our healthcare system. This initiative was captured in a final document with various recommendations.1 Recently, a summary was published as a special article in an issue of REVISTA CLINICA ESPAÑOLA.2

In general, changes to improve the quality of healthcare systems in Western countries come slowly and are plagued by difficulties: they are care structures comprising multiple professionals whose management—human, technological, and organizational—entail a high degree of complexity.

Some barriers to innovation in healthcare systems can be explained by the fact that they have antiquated organizations, infrastructures, regulatory rules, and incentive systems; by fragmentation and institutional and corporate stagnation; by a lack of up-to-date knowledge about technology and processes already adopted by other sectors; by human beings’ natural skepticism and refusal to modify routines; and lastly, because practical incorporation is very difficult.

In short, resistance to change depends on the initiatives proposed, how they are put into practice, the characteristics of the professionals involved, different organizational factors, and the nature and context of the environment.3

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection in recent months—one of the greatest epidemics in the history of mankind with millions affected and hundreds of thousands of deaths—has obligated healthcare systems to make radical transformations in order to face this global pandemic.4 Some consequences have been the modification of hospital structures and care management; the restriction of social mobility by regulations issued by the authorities to reduce transmission of the infection; and patients’ and the population's fear of infection if they came to healthcare centers. Along with the role of professionals, the role of citizens as a driving force for change in all aspects has been essential. Their responsibility in self-care, compliance with social isolation, and rational use of healthcare resources are noteworthy.

This very powerful change in the environment has broken down pre-existing barriers to innovation, which have been overrun by the urgent nature of the search for solutions in healthcare, both on the general and local levels.5 This transformation has been so substantial that it can be considered disruptive, as it has completely broken the previous paradigm and forced us to reconsider the premises and care models that have been in place up to now.

In these weeks, we have frequently read that “nothing will be like it was before,” and certainly, in regard to healthcare, it is possible that many of the changes urgently implemented due to the COVID-19 infection are here to stay.

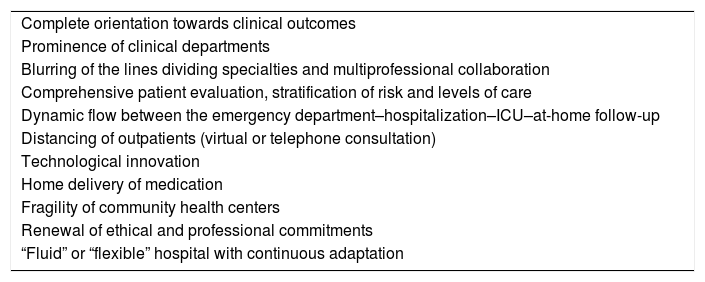

A large part of the “hospital of the future” recommendations have been incorporated quickly and naturally into hospitals during the pandemic (Table 1). Among them, the clinical departments that have led the centers have had special prominence, providing guidance on the needs for infrastructure, patient flows, and necessary materials.

Lessons from the COVID-19 disease.

| Complete orientation towards clinical outcomes |

| Prominence of clinical departments |

| Blurring of the lines dividing specialties and multiprofessional collaboration |

| Comprehensive patient evaluation, stratification of risk and levels of care |

| Dynamic flow between the emergency department–hospitalization–ICU–at-home follow-up |

| Distancing of outpatients (virtual or telephone consultation) |

| Technological innovation |

| Home delivery of medication |

| Fragility of community health centers |

| Renewal of ethical and professional commitments |

| “Fluid” or “flexible” hospital with continuous adaptation |

Due to their versatility, their degree of qualification, and their great capacity for adaptation, the internal medicine departments, present in all hospitals, have been one of the main protagonists in confronting COVID-19 in Spain and other countries. Furthermore, there has been a blurring of lines between traditional medical specialties with the establishment of multiprofessional groups or “COVID teams,” with the active participation of nursing departments, which have played new roles.

The consideration of ethical and professional duties to patients, their families, and society has taken precedence over any other circumstance, which has meant a renewal of healthcare professionals’ ethical commitments.

The initial comprehensive evaluation, the consideration of individual risk, and the stratification of levels of care have been the rules for procedure in assigning available care resources in the most appropriate manner according to each center’s changing circumstances.

The clinical pathways of patients between emergency departments, hospitalization wards, intermediate or critical care units, and at-home follow-up—managed either from the hospital or from primary care—have been more fluid than ever. Furthermore, novel shared care tools have been implemented. The close coordination among clinical departments, laboratories, and radiology departments has provided solutions for making quick clinical decisions with a reduction in response times.

Hospitals have become coordination centers for care and for performing diagnostic tests on a massive scale. They have also taken charge of the medicalization of community health centers and nursing homes and of the launch of field hospitals or pavilions in order to increase available hospital beds.

In the direct care of hospitalized patients, digitalization and telemedicine initiatives have been implemented or expanded. These include the telemonitoring of conventional hospitalization wards, performing electrocardiograms with small devices that are easy to use and sterilize, and through telemedicine or virtual consultations in order to increase the number of visits while reducing professionals’ exposure and the use of protective equipment as well as phone calls via mobile devices to the patient or family.6

Physicians performing bedside ultrasounds has become an essential tool for monitoring the progress of COVID-19 infection with lung involvement.7 At-home follow-up of intermediate-risk patients who are not hospitalized has been carried out in many centers, with their active participation and the help of devices for monitoring oximetry, video calls, and structured interviews.

The distancing of outpatients with this disease as well as other pathologies has been solved in large part by collecting samples in special devices or at home, by virtual telephone consultations when remote access is available to the complete electronic medical record, and with at-home delivery of medication used in hospitals. Geolocalization has been used for studying contact and to ensure social distancing. In short, different types of telemedicine and communications technology have undergone an exponential expansion in just a few weeks.8,9

Continuous transformation in order to provide solutions has made a “fluid” or “flexible” hospital model with constant adaptation to different scenarios obligatory. The different initiatives have not been exempt from difficulties or problems nor is the impact of the pandemic on global health outcomes or on other pathologies known yet. These aspects must be analyzed carefully in the coming months. In any case, we can say in that in many aspects, the hospital of the future is already here; it has been brought by the COVID-19 disease.

Within the drama that has caused such personal and collective suffering and the consequent economic catastrophe, we must draw the best lessons learned so as to improve the healthcare system as a whole. We need to make it more approachable and adaptable to patients’ needs in order to avoid unnecessary clinical procedures and in-person visits and, definitively, to make it more personalized, efficient, and of a higher quality.

On the other hand, the obligation to break with the current rift between what is societal and what is healthcare is imperative, as our surroundings have revealed its great fragility and how arbitrary this separation is. Some unavoidable lessons that must be tackled include strengthening the healthcare system as a whole and ensuring it is prepared to simultaneously face possible future healthcare crises due to communicable diseases and new outbreaks of SARS-CoV-2 or other zoonotic diseases, avoiding the epidemiological unpreparedness that we have endured.10 All of this must be combined with appropriate attention to another less-recognized—or “silent”—pandemic of chronicity, multimorbidity, and the aging of the Spanish population.

This process must be done cautiously through shared reflection in hospitals along with primary care and healthcare authorities. Standardized working procedures and regulatory rules must be established with due recognition of our actions and new professional roles as well as of different care models.

Please cite this article as: García-Alegría J, Gómez-Huelgas R. Enfermedad COVID-19: el hospital del futuro ya está aquí. Rev Clin Esp. 2020;220:439–441.